20 April 2024

Louisa Ghevaert was delighted to attend Progress Educational Trust’s event “Mary Warnock at 100: The Architect of Embryo Law” on 17 April 2024. This event looked at the continued influence of Baroness Mary Warnock DBE, one of our most significant twentieth century philosophers, in the field of fertility. Mary died age 94 in 2019. However, her work on bioethics and her legacy lives on having fundamentally shaped law, policy and practice for assisted reproductive technology in the UK and around the world.

The first speaker was Felix Warnock who gave a fascinating introduction and insight into the life and work of his mother Mary Warnock. He explained that he was one of Mary’s five children (an achievement in itself) and that she combined her role as mother with being a professional philosopher with verve and vigour. He went on to say that Mary was unusual in that she was very interested in practical outcomes and not just theory. As a result she became a “philosophical plumber” to the Establishment and she was trusted and relied upon to get things done. Politicians frequently asked her about ethical issues, placing their trust in her to know right from wrong. He described her as a positive force and an optimist who engaged broad public support. In doing so, she was the architect of the 14-day rule (enabling research on human embryos up to 14 days after their creation), which has endured and enabled the development of fertility treatment and research up to this point in the UK.

Image: Felix Warnock, son of the late Baroness Mary Warnock DBE and Administrator at the Mental Health, Ethics and Law Research Group at King’s College London

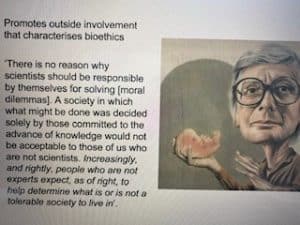

The next speaker was Dr Duncan Wilson, Senior Lecturer at the University of Manchester’s Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine. He explained that Mary was such a well known and influential figure that she featured in a cartoon in the Sunday Telegraphy newspaper. She was chosen to lead the government committee of inquiry into reproductive technology (1982 – 1984) which determined the fate of laboratory human embryos and formed the basis of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990. She was appointed to this position because she had already headed an inquiry into special educational needs and related public policy. She was seen as an ‘outsider’ without connections to IVF or embryology technology and the government felt that outside scrutiny was the best route to ensuring public accountability. She was also the first non-expert to chair a government inquiry (prior to this they always appointed an expert in the field).

Image: Dr Duncan Wilson, Senior Lecturer at the University of Manchester’s Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine

Dr Wilson explained that central to Mary’s work and success was her ability to promote outside involvement, although she brought scientists and medics along with her too. She took the view that developing suitable bioethics was critical for medicine and science, but this should not just be the responsibility of scientists saying “There is no reason why scientists should be responsible by themselves for solving [moral dilemmas]. A society in which what might be done was decided solely by those committed to the advance of knowledge would not be acceptable to those of us who are not scientists. Increasingly, and rightly, people who are not experts expect, as of right, to help determine what is or is not a tolerable society to live in”. He went on to explain that her work secured public and political trust and oversight of reproductive technologies and ensured that “no nameless horrors were going on, hidden away in laboratories”.

Dr Wilson explained that Mary was very adept at positioning herself and bioethics as an intermediary between the public and the scientific and medical professions and that she “sold bioethics” with her pragmatic approach to regulating embryo research. She carefully, clearly and concisely explained that the 14-day embryo research limit coincided with the primitive streak and that there was no possibility at this point that it could feel pain. She also emphasised that it should not be seen as an individual then because it was still a collection of cells that could still divide into twins or triplets. Her work went on to underpin a regulatory framework for embryo research and fertility treatment that endures to this day.

The next speaker, Professor Ann Mastrioiami of Bioethics and Law at the Berman Institute of Bioethics at Johns Hopkins University, gave fascinating insight into the Warnock Report’s influence on US bioethics policy. She explained that Mary’s work was influential in that the Warnock Report became a reference point in the US despite there being around 85 other reports within ten years of the birth of the world’s first IVF baby Louise Brown in 1978. The Warnock Report was repeatedly referred to in US committees and it helped explain the rationale behind the 14-day limit for embryo research. However, in the US they encountered a very entrenched position led by anti-abortion advocates which meant that even now there is no comprehensive Federal Law governing embryo research and treatment. Instead, each US regulates its own approach to embryo research and fertility treatment.

Following this, Baroness Ruth Deech Crossbench Peer in the House of Lords and Chair of the House of Lords Appointments Commission gave some personal insight into the life and work of Mary Warnock. She described Mary as being utterly assured, with a toughness that was impervious to slights. She went on to say that nothing stood in Mary’s way as an elite Oxford University graduate and that she moved in three overlapping circles. She was part of a group of Oxford Women’s philosophers and she put her philosophy to practical use. Her views prevailed in the House of Lords and she was very influential in Parliament during the inquiry and up to the passing of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 which for 30 years has held good in reproductive science. Baroness Deech also explained that Mary emphasised the rule of law whilst opposing bans on all embryo research and stressing the need for continuing research. She also demonstrated the ability of parliamentary committees to look at difficult issues and summed her up as the “original quango queen” and a member of the “great and good“.

Images: Professor Ann Mastrioiami of Bioethics and Law at the Berman Institute of Bioethics at Johns Hopkins University and Baroness Ruth Deech Crossbench Peer in the House of Lords and Chair of the House of Lords Appointments Commission

The final speaker was Julia Chain, current Chair of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). Julia explained that The Warnock Report sought protection for the public in the face of rapidly evolving reproductive technology and demanded the establishment of a new authority to regulate fertility treatment and research. In doing so, Mary foresaw the need for regulation as a necessary bargain between science and society. As a result, the HFEA comprises both lay and professional members so that its decisions are informed by expert opinion but not dominated by it. She went on to say that the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 is now out of date and it needs to be reviewed and modernised to reflect the needs of today as science and medicine has developed and because our thinking about what is socially acceptable has changed. We now have a wide range of family forms, whereas the Warnock Report only recognised married or co-habiting heterosexual couples. We also need a more sophisticated confidentiality regulatory framework to enable transfer of medical records and deal with the reality that donors can be traced through at-home DNA tests. Furthermore, she explained that changes need to be made to the way we regulate the fertility market as two thirds of it are now operated privately and backed by large private equity groups, which is very different to the market place 30-40 years ago. Lastly, she explained that we need to future proof the law by ensuring that we do not make it too prescriptive to deal with scientific advances including artificial embryo models and in vitro derived gametes. As such, she concluded that Mary understood the importance of public consultation and the HFEA continues to aim to achieve ethical consensus. She described Mary as a “visionary” who was very much “of her time”.

Need Advisory & Consultancy, a Fertility, Surrogacy, Donor Conception or Modern Family Lawyer?

Images: Louisa Ghevaert CEO & Founder Louisa Ghevaert Associates